“Is that your final answer?” That famous phrase heard worldwide in different languages on the wildly popular game show “Who Wants To Be a Millionaire?” meant that the time had come to make a final decision. Viewers sweated and felt the knotted stomach of emotional tension in the contestant. In my previous articles on decision-making, we’ve explored ways to prepare for making a decision–18 cognitive biases and mental shortcuts that can derail our decision process, 7 ways to overcome confirmation bias, and 5 methods to create more choices. Now it’s time to conquer the emotional bias when asked, “Is this your final answer?”

After we’ve done our due diligence research, expanded our options, and searched for disconfirming evidence, the biggest challenge at the moment of decision is to control our emotions. As we currently understand the brain, we have a quick reaction System 1 that is linked to our short-term emotional responses. This “experiential system” subconsciously uses past experiences and the emotions associated with them to assess risk. Often, this system works well and helps to respond to the myriads of inputs to our brain without becoming overwhelmed…but emotions can sidetrack, or even skip, the rational decision-making process that occurs in System 2.

The “analytical system” uses conscious, deliberate processes using algorithms and standard rules to lead to logical behavior. When we make decisions, we weigh the risk and reward of various options. The input from System 1 to that risk/reward valuation can fluctuate under different emotional conditions. To make the most effective choices, we need to be aware of how emotions bias our decisions, and then try to appropriately control them.

The goal is not to make emotionless decisions—after all, emotions are naturally part of being human. But to take better charge of our choices, we can use the 5 techniques below to help control emotions in the critical decision time.

5 Emotional Saboteurs of Logical Decisions

First, let’s a review some of the most relevant biases that are emotional saboteurs of good decisions:

1. Mere Exposure Effect (Familiarity Principle)— People develop a preference for things that are more familiar.

There’s a saying in Western culture, “familiarity breeds contempt.” It means the more we know about someone or something, the more we’ll see the negative side. But the opposite is probably more often true. Our minds become programmed to accept and like things to which we’re frequently exposed. Given no other information, we’re more likely to choose a brand we know, over a strange brand.

Familiarity doesn’t mean risk-free, though. We make poor choices if we only rely on the emotional comfort of the familiar to make a decision. An investor chooses a well-known stock, but ignores higher performing unfamiliar investments. A person stays in an abusive relationship because they are accustomed to the behavior. The familiarity may be subconscious, but it can influence us to make an emotion-based decision first, and then rationalize the choice afterwards.

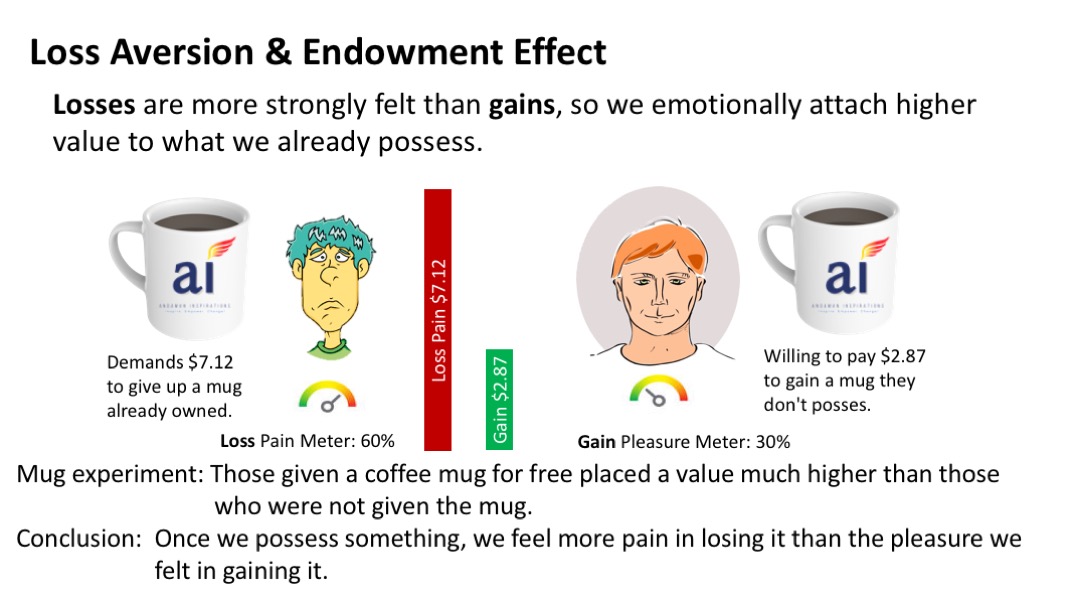

2. Loss Aversion & Endowment Effect—We find losses more painful than gains are pleasant; we emotionally attach higher value to what we already possess.

Behavioral economists have performed various experiments to test this concept, a well-known one being the “Mug Experiment.” Subjects were divided into 2 groups, and one group was given coffee mugs as a gift. They were then asked to put a price value on the mugs. The other group, that had not been given anything, was asked to put a price value on the same mug. Those already in possession of the mug valued it significantly higher than the second group. ($7.12 versus $2.87) Companies use this effect frequently to influence our buying decisions by giving “free trial periods;” even though they allow a return or cancellation, loss aversion prompts us to keep and pay for the product or service.

3. Exaggerated Emotional Coherence – The Halo Effect. Once we feel a certain way about a particular aspect of something, we tend to feel the same way about all aspects of it–including things we have not observed.

We might see someone sharply dressed, with a confident posture, handsome looks, and charming smile, giving a positive emotional first impression. Because our mind, particularly in System 1, is constantly trying to make sense of the world, it fills in blanks to make a coherent story. We might easily fill in a story that the person is intelligent, kind, and generous based on the first impression.

In one experiment, a group of subjects was given a 6-word description of a person in order from positive to negative characteristics. A second group was given the same 6-word description, but starting with the negative characteristics. The first group felt they “liked” the fictitious person more, because they started liking from the initial positive words.

The lesson for decision-making is that we may have a positive feeling toward one choice over another simply because we liked one aspect of that option, and let that emotion carry over to the entire choice.

4. Affect (Experience of Feeling or Emotion) Mental Shortcut — people let their likes and dislikes determine their beliefs about the world.

We tend to substitute the easier question “How do I feel about it?” when faced with the harder question, “What do I think about it?” Especially if we’re pressed for time on a decision, we more easily go with our “gut feeling” than analysis.

In one study, researchers asked subjects to estimate the nutrition level of a breakfast cereal marketed at kids, called Coco Pops. Those who had grown up eating the cereal, and seen commercials of the cute and fun Coco Pops monkey, rated the nutrition level (quite inaccurately) much higher than those who had never been exposed to the cereal. They had allowed their positive childhood emotions to make a judgment about how they felt about the cereal, rather than engage their analytical mind.

5. Projection Bias — We overestimate both the intensity and duration of our emotions in the future.

Our present selves don’t really know our future selves very well. We think that winning the lottery will make us ecstatic for many years, when in fact winning has very short-term effects on happiness. Or, we think that life would be unbearable without our spouse, but most people report their level of happiness isn’t changed nearly as much as expected after a divorce or death of spouse.

Psychologist Daniel Gilbert calls this “affective forecasting” and demonstrates that we’re not very good at it. A simple experiment interviewing concert-goers about their favorite band from 10 years before showed that they would not be willing to pay very much to see that band now. But in the same interview, when asked how much they would pay 10 years in the future to see their current favorite band, they projected being willing to pay a very high price—ignoring the implications from the first question.

In this podcast by Dan Heath, Olympic skiing champion Diann Roffe tells her story of achieving her gold medal dream, and dealing with the over-expectations of her happiness in winning, while quadriplegic Scott Fedor recounts the tragedy of his disabling accident and his ability to overcome the extreme despair he foresaw in his life when he was first injured. Diann struggled in family and professional life after her gold medal victory, which she had expected would change her life to be much better. Scott was asked by the doctor whether he wanted to live after his accident, and given the choice to be taken off of life support. Facing a life of paralysis, he nearly succumbed—but now leads a life inspiring others. It’s fortunate for us when we hit hard times that we overestimate negative emotions; yet, it also illustrates that forecasting emotional states when considering a decision can be very challenging.

Victory is not as sweet, nor defeat so bitter, as we project in our minds. 1994 Olympic Super G ski champion Diann Roffe, and motivational speaker Scott Fedor.

In all of these above areas, emotional impact can make us ignore risks and exaggerate the benefits of things we like, while we overly fear risk or exaggerate the downside for things we don’t like. The following five techniques help us gain emotional control over our decisions.

5 Techniques to Control Emotional Bias

1. Use Perspective of Time.

In Back to the Future, the popular series of science fiction movies from the 80s, characters travel back and forth through time, able to get a different perspective on themselves and those close to them. Similarly, using imagination to take ourselves out of the present can help us control emotions.

Author Suzy Welch promotes a technique of imagining the consequences of a decision in 10 minutes, 10 months, and 10 years in the future…her “10/10/10” rule. This method can be good for escaping the immediate emotion of the moment. The more detailed and richer we can imagine those future consequences, the more effective this method could be…but it also suffers from a serious flaw in humans: we are particularly bad at predicting our future selves (Projection Bias).

Psychologist Dan Gilbert says in an interview, “We and many others have spent decades trying to figure out, how can we make human imagination better? If when people look into the future, they make mistakes, what kind of training could we give them so they don’t make these mistakes? And I will give you the summary of 15 years of research – it doesn’t work.” He finds what does work, however, is finding people who could be the “future you”…people who have faced a similar decision in the past. Making a career choice, a relocation, a particular type of investment—it may take some work to find the right people, but we can apply this advice in many different types of decisions.

2. Use Perspective of Place.

Aside from stepping outside the time of decision, we can also take an outsider’s view. People often give better, more objective advice to their friends than they give to themselves, and it can be helpful to think of yourself in the 3rd person—as someone else helping to guide you. When an outsider gives us advice, they don’t share the same emotional investment in a decision, and from a more distant perspective, may be able to see the big picture “forest” while we are only seeing the detailed “trees.” The 3rd person perspective focuses on the most important aspects of a problem, rather than details with emotional pull.

Researchers in Michigan found that using one’s own name, or a 3rd person pronoun (he or she) in self-talk helped decrease activity in the brain associated with negative emotions. “Essentially, we think referring to yourself in the third person leads people to think about themselves more similar to how they think about others…. That helps people gain a tiny bit of psychological distance from their experiences, which can often be useful for regulating emotions,” according to psychology professor Jason Moser.

In 2010 basketball superstar LeBron James was widely criticized online for referring to himself in the 3rd person when talking about a decision to leave one team for another, but in fact he was using this method to distance himself from his emotions. “I didn’t want to make an emotional decision. I wanted to do what was best for LeBron James and what would make him happy,” LeBron said. So don’t be shy about having conversations with yourself—it’s not a sign that you’re crazy!

3. Let’s Get Physical: Decide When the Body is Ready

It’s perhaps too easy to think of our brain and cognitive processes as separate from the rest of our body, but biological and neuroscience research have shown our physical being is an integrated whole. The circadian rhythm describes the constant, regular fluctuation of many body parameters, such as temperature, blood pressure, and hormone levels, and these changes affect mood. In his most recent book, When: The Scientific Secrets of Perfect Timing, psychologist Daniel Pink identifies three main stages that we move through each day: Peak, Trough, Recovery.

In a podcast interview, Pink explains that most people have an elevated mood in the morning which would be good for making decisions requiring strict analysis. The mid-day trough is probably least conducive to making decisions. A study of 26,000 earnings calls (calls made by companies to shareholders to report on earnings) showed that afternoon calls had more negative emotional content and caused a temporary dip in stock price. The recovery period later in the day, however, sees a resurgence in mood, with less inhibition, and so would be a time for making decisions that require a little more creativity. Happy moods, however, need to be treated with caution as well. Abundant studies demonstrate that elevated moods tend to make us more prone to take risks and to dismiss warning signs.

The higher level thinking processes of our brain require considerable energy, which must come from the body’s content of blood glucose that powers the brain. Thus, the nutrition cycle is an important factor in decision-making. Behavioral economist Daniel Kahneman found that judges granted parole at a higher rate just after lunch, and then declined in correlation with time as their nutritional stores depleted. His conclusion was that the decrease in mental energy caused the judges to spend less analysis on each case, and go with a “safer” choice of not granting paroles. Subsequent research has shown a more complex relationship of hunger and risk taking. One study showed financial risk-seeking behavior increased when one was hungry. But other evidence showed that a particular class of people who normally tend to be risk-seeking, actually become more risk-averse when hungry.  Besides minding our glucose levels at the moment of decision, we also need to be aware of our state of rest. Total sleep deprivation, i.e. having an accumulated lack of sleep because of circumstances such as night shifts, long hours, etc., has a significant impact on our cognitive ability. A meta-study (a study of sleep deprivation studies) found that total sleep deprivation increased rigid thinking and decreased the ability to use “new information in complex tasks requiring innovative decision-making.” Lacking sleep also led to less strategic thinking and increased risky behavior. Each person’s physical rhythms will be different, but we can’t ignore the link between mood, hunger, and rest when it’s time to make important choices.

Besides minding our glucose levels at the moment of decision, we also need to be aware of our state of rest. Total sleep deprivation, i.e. having an accumulated lack of sleep because of circumstances such as night shifts, long hours, etc., has a significant impact on our cognitive ability. A meta-study (a study of sleep deprivation studies) found that total sleep deprivation increased rigid thinking and decreased the ability to use “new information in complex tasks requiring innovative decision-making.” Lacking sleep also led to less strategic thinking and increased risky behavior. Each person’s physical rhythms will be different, but we can’t ignore the link between mood, hunger, and rest when it’s time to make important choices.

4. Learn to Detach From Sunk Costs.

Sunk costs are unrecoverable expenditures of time, effort, and money we have already invested in some venture. Economists tell us that we must not consider sunk costs when making decisions about the future—that we must assess risks on their own merits and detach from the past. But this concept can feel counter-intuitive. Our problem is that we become emotionally attached to our goals and the efforts that we put into them.

A tragic incident on the top of the world in 1996 illustrates the consequences of counting sunk cost. Doug Hansen was a 46-year-old postal worker from Seattle with a dream of conquering Mount Everest. Though he had limited funds for a venture that cost many tens of thousands of dollars, he relentlessly pursued his goal. Unfortunately, he was turned back 110 meters from the summit in his first attempt at Everest in 1995. During his second attempt the following year, he was even more determined to succeed, saying “I’ve put too much of myself into this mountain to quit now without giving it everything I’ve got.”

A tragic incident on the top of the world in 1996 illustrates the consequences of counting sunk cost. Doug Hansen was a 46-year-old postal worker from Seattle with a dream of conquering Mount Everest. Though he had limited funds for a venture that cost many tens of thousands of dollars, he relentlessly pursued his goal. Unfortunately, he was turned back 110 meters from the summit in his first attempt at Everest in 1995. During his second attempt the following year, he was even more determined to succeed, saying “I’ve put too much of myself into this mountain to quit now without giving it everything I’ve got.”

Rob Hall was his renowned, highly-experienced guide. Rob had turned Doug back in the 1995 expedition, and was heavily invested in seeing Doug succeed. With reports of heavy weather approaching, Rob’s group had planned a hard turnaround time: if they had not reached the summit by 2 pm, it was time to turn around.

Above 8000 meters (26,247 feet) is called the “Death Zone” by climbers, because there is not enough oxygen for normal humans to breathe; even with supplemental oxygen, cognitive abilities can be hampered. Extreme altitude causes many other deadly problems associated with the lungs and brain. It’s critical to make hard decisions like turnaround times in advance before entering the death zone.

Delays behind other climbers meant that Rob’s group had not yet reached the peak by 2 pm, but Hall decided to continue. Hansen wouldn’t reach the top until about 4 pm. But in the death zone, Doug had begun to succumb to its perils, possibly a swelling of the brain. He collapsed on descent not very far from the top, unable to continue. Rob stayed to assist him, until a fierce storm of super hurricane force prevented him from descending. Both perished in the storm.

Doug Hansen and Rob HallEffective decisions must control emotions and ignore sunk costs. When we emotionally attach ourselves to sunk costs, it’s like making excuses for decisions already made, rather than making a decision based on the future. The 2 pm tripwire should have helped to take the emotion out of Hall’s and Hansen’s decision to safely turn back, but it’s quite likely the thought of how much effort had been spent to get so tantalizingly close overpowered more rational thought. In the same way, we need to make decisions based on analysis of current resources, not what’s already been spent, and assess the present risk versus reward of our decision.

5. Establish and Honor Your Core Values.

MIT professor William Pounds interviewed numerous managers in one study to find out what their most important problems were. After identifying these problems, the managers were further queried about their daily activities. According to Dr. Pound, “no manager reported any activity which could be directly associated with the problems he had described.” (from Decisive by Dan & Chip Heath). Those managers had not scheduled any time for their core priorities. People often let the urgent overwhelm the important. When time or other resources are short, studies show that we more often allow the automatic, emotion-connected System 1 to dominate our decisions.

Many successful leaders organize their schedules constantly assessing their priorities. Global consultants Rasmus Hougard and Jacqueline Carter recommend looking at goals and priorities from a monthly, weekly, and then daily perspective. The have a 2/2/2 technique for the start of each work day. The first 2 minutes start with a mindfulness practice, such as meditation, to create focus. The second two minutes are for prioritization, identifying the limited amount of important things that must get done that day, which are derived from the previously identified purpose and principles. The final two minutes are a planning exercise, which is in many ways a trimming exercise. It involves ruthlessly cutting activities that aren’t contributing to the priorities. Business author James Collins recommends making a “Stop-Doing” list of things that get in the way of our priorities in life. This recognizes that every activity we do has an opportunity cost. The time spent working on something of lower priority is opportunity lost to spend those minutes or hours on something more important. Time is a resource that can’t be purchased or refunded!

Many successful leaders organize their schedules constantly assessing their priorities. Global consultants Rasmus Hougard and Jacqueline Carter recommend looking at goals and priorities from a monthly, weekly, and then daily perspective. The have a 2/2/2 technique for the start of each work day. The first 2 minutes start with a mindfulness practice, such as meditation, to create focus. The second two minutes are for prioritization, identifying the limited amount of important things that must get done that day, which are derived from the previously identified purpose and principles. The final two minutes are a planning exercise, which is in many ways a trimming exercise. It involves ruthlessly cutting activities that aren’t contributing to the priorities. Business author James Collins recommends making a “Stop-Doing” list of things that get in the way of our priorities in life. This recognizes that every activity we do has an opportunity cost. The time spent working on something of lower priority is opportunity lost to spend those minutes or hours on something more important. Time is a resource that can’t be purchased or refunded!

Making good decisions can be tough, and we face many challenges from our own emotional biases—liking things just because they’re familiar, over-valuing things that have come into our possession and exaggerating our fear of loss, filling in unknown information without factual basis just because we have a positive first impression, allowing our feelings to substitute for analytical thinking, and inaccurately predicting our future emotional state. Stepping back from the moment of decision to get a long-term view, from an outside perspective, can help balance the emotional impact of decisions. Paying attention to our physical state, ensuring that it is primed for optimal effectiveness, also helps. We look toward the future, not counting unrecoverable expenditures of effort, time, or money. Finally, we write down and stick to our core principles, fighting daily to prioritize the things that matter. If you have your own methods or ideas about controlling emotions in decision making, or would like to start a conversation on ideas discussed above, please share below in the “Leave a Reply” box. I’d love to hear from you!